I’ve started to get a decent grasp of front-end web development and some of the popular tools that are available to facilitate the process. However, my experience up until this point has been limited to Github Pages. I’m curious about that other, server-side piece.

Recently, I’ve taken on a project I’d like to host outside of Github. A new experience! We’re going to take a look at that process here. My project is a static business landing page with some javascript elements, so it feels like it will be a good test-case. To build the site, I used the toolkit I wrote about here, including Jekyll, Bootstrap and Sass. I’ve tested it out locally & I’m satisfied with how it looks, so let’s look at publishing it online.

From this list of free webhosting services, I chose to work with infinityfree.net due to its fast advertised load times & forever-free service.

File Transfer with FTP

Logging into our brand new InfinityFree account, we’re met with a plethora of admin tabs and configuration options – definitely a little overwhelming at first. First, we create a new hosting account under the Accounts tab and select Manage, which takes us to our site dashboard. From here, our next step is to figure out how to upload our file tree. InfinityFree recommends uploading files with FTP, which is a relatively new concept for me.

On the other hand, FTP (File Transfer Protocol) is an old concept in the history of the internet. In fact, first developed for ARPANET, FTP predates the internet itself. It is the longest-standing internet protocol; it’s also not really secure at all. The only ARPANET users were researchers vetted by their institutions, so of course it wasn’t developed with data security in mind. FTP does not use encryption, and data is sent in plaintext – usernames & passwords included. There are secure alternatives such as FTPS, or tunneling FTP through an SSH connection. But I’m no expert on that yet, and that’s not why we’re here.

To set up our FTP connection, we’ll need a username & password, which InfinityFree generates for us. We’ll also need to know the FTP address InfinityFree will use for our account.

All these can be found on our site dashboard under FTP Details (app.infinityfree.net/accounts/your_username).

Next, we’ll need an FTP client to send our server requests for us. InfinityFree’s tutorial suggests FileZilla, but to be honest, I don’t think we need an entire GUI for this. It would be convenient to be able to transfer files without leaving the command line. A quick search on Homebrew (Apple’s package manager) suggests git-ftp, which sounds promising.

$ brew search ftp

==> Formulae

bbftp-client lftp pure-ftpd

curlftpfs ncftp swift-protobuf

git-ftp ✔ proftpd swiftplate

According to its description, git-ftp integrates with our project’s Git environment to determine file changes to upload. This FTP client was developed for Linux, but it could easily work on other systems, right? Sounds handy enough, so let’s try it out.

$ brew install git-ftp

It’s also available on Github or its website.

To start, we pass git-ftp the FTP credentials we collected earlier.

$ git config git-ftp.user "your-ftp-username"

$ git config git-ftp.password "your-ftp-password"

As for the FTP address, InfinityFree gives us the plain URL ftpupload.net. If we type this into a browser as is, we’ll get a “connection refused” error because browsers assume HTTP or HTTPS protocols, not FTP.

Most modern browsers do include an FTP interpreter we can apply as long as we specify the protocol:

ftp://ftpupload.net

This will load a hyperlinked view of the FTP server’s file tree for our username. By default, InfinityFree generates a couple files (for example, DO NOT UPLOAD FILES HERE) as well as an htdocs/ folder, which is where we should upload our site files.

Let’s pass that on to git-ftp.

$ git config git-ftp.url "ftp://ftpupload.net/htdocs/"

It’s worth noting that up until this point, these are purely git commands – we’re just defining some new variables in our .git/config file.

$ less .git/config

[core]

repositoryformatversion = 0

filemode = true

bare = false

logallrefupdates = true

ignorecase = true

precomposeunicode = true

[branch "main"]

merge = refs/heads/main

[git-ftp]

url = ftp://ftpupload.net/htdocs/

user = your-ftp-username

password = your-ftp-password

Next we’ll see the real magic. To upload our site files,

$ git ftp init

7 files to sync:

[1 of 7] Buffered for upload '.gitignore'.

[2 of 7] Buffered for upload '.ruby-version'.

[3 of 7] Buffered for upload 'Gemfile'.

[4 of 7] Buffered for upload 'Gemfile.lock'.

[5 of 7] Buffered for upload 'LICENCE'.

[6 of 7] Buffered for upload 'README.md'.

[7 of 7] Buffered for upload '_config.yml'.

Uploading ...

Last deployment changed from to [hash].

Here, we see that git-ftp has actually added the ftp sub-command to Git itself – pretty cool! Now, if we refresh ftp://ftpupload.net/htdocs/ in our browser, we’ll see the updated file tree, including our site files.

Jekyll Build

At this point, we can check out our site as well, and as long as we’ve uploaded an index.html, we’ll see its contents replacing the default splash screen! (Images and bulky files may take a few minutes to load.)

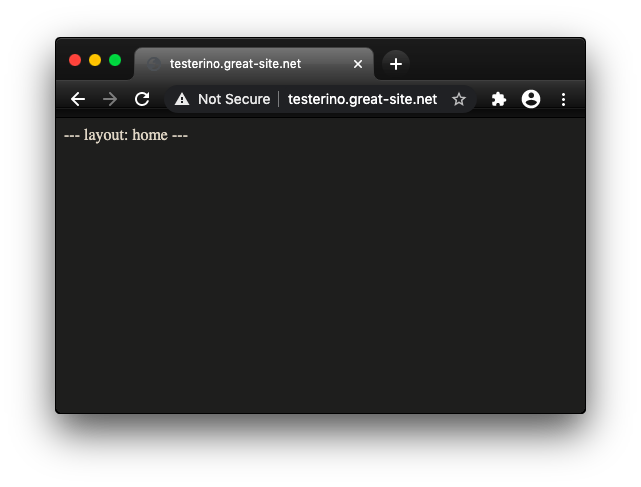

Of course, for me, getting the desired result was not so simple. All I got to see was:

… which is simply the layout template call in my development site’s index.html.

We’ll need to precompile our production site if we use tools like Jekyll, Sass, React, etc. I’ve been spoiled so far by Jekyll’s integration with Github Pages, so this hadn’t come up for me before.

Building with Jekyll is easy enough, though.

$ bundle exec jekyll build

This generates our production site in the _site folder in project root.

Now we need a way to tell git-ftp to send our _site contents instead of the entire repo.

There should absolutely be a

git-ftpoption to send a folder contents to remote home, but unless I’m mistaken, there doesn’t appear to be one yet.

That’s okay though – we have a couple other options.

Manual Setup

We could declare a new Git branch in which we manually replace development files with our production site files. A clunky solution, fine for a one-time upload, but otherwise worth automating. FileZilla is probably a better option than this.

With Github Actions

We could automate the above process with the Github Action I wrote about here.

Jekyll-action updates its own branch with our _site contents whenever we push changes to main.

This requires pushing our site to a Github remote repo and fetching the Action-generated branch whenever we’d like to publish changes.

After setting up jekyll-action,

$ git push

$ git fetch generated-branch

$ git ftp push -b generated-branch

It’s not ideal, having to upload our site files to both Github and FTPUpload, and the setup for jekyll-action is a bit involved as well; but we can at least keep our Github repo private if desired.

With Git Submodules

We could declare a new Git repo within _site and push that repo to the FTP site. For nested repositories, Git recommends their submodule functionality.

To set up a submodule, first initialize the _site repo:

$ cd _site

$ git init

$ git add .

$ git commit -m "First commit."

Then return to the parent repository, and add _site as a submodule.

$ cd ..

$ git submodule add ./_site

From here, we’re free to setup git-ftp within our submodule as above.

$ cd _site

$ git config git-ftp.user "your-ftp-username"

$ git config git-ftp.password "your-ftp-password"

$ git config git-ftp.url "ftp://ftpupload.net/htdocs/"

$ git ftp init

Whenever we make changes to our development build (the parent module), all we need to do is generate a new production build and push it to FTP.

Jekyll leaves our submodule .git settings intact between builds, so our publishing workflow becomes

$ bundle exec jekyll build

$ cd _site

$ git add .

$ git commit -m "Commit message."

$ git ftp push

This is my favourite workflow solution of the three. It minimizes our toolset, only relying on Git and git-ftp (plus whichever precompiler you develop with). The setup is straightforward and intuitive, and fully contained within our CLI.

With that, we’ve developed a basic but functional workflow for publishing static sites with a non-Github hosting service. Although we’ve only scratched the surface of server-side processes, we got our first taste, and a new sandbox to learn in.

You can check out my published site here.